The region historically known as Bengal—the combined geography of present-day West Bengal (India) and Bangladesh—encompasses an extraordinary diversity of landforms and ecosystems. These range from mountains and Himalayan foothills in the north to vast floodplains, grasslands, wetlands, river systems, estuaries, and the iconic Sundarbans mangrove delta in the south.

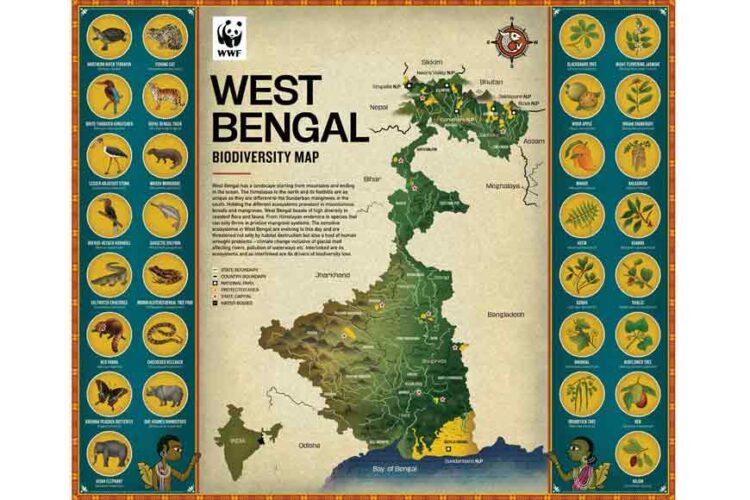

Northern West Bengal (Darjeeling, Kalimpong, and parts of Jalpaiguri and Alipurduar) contains authentic Eastern Himalayan ecosystems, including temperate and subtropical broadleaf forests, montane cloud forests, and exceptional biodiversity. The region is home to red pandas, numerous Himalayan bird species, orchids, and many other endemic plants and animals.

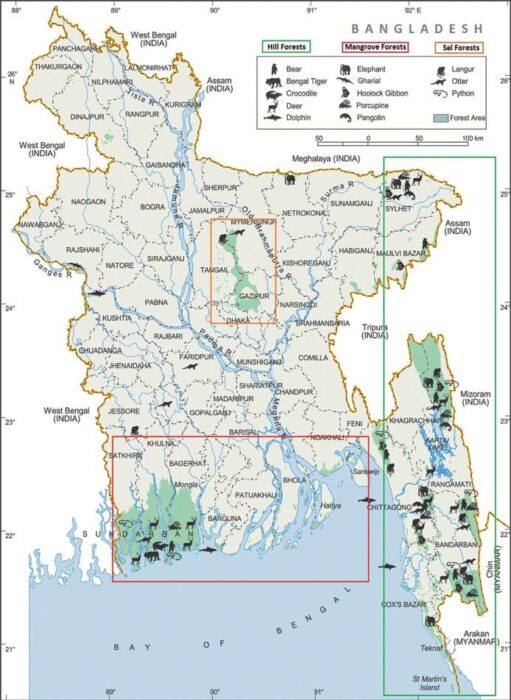

In contrast, Bangladesh is predominantly a lowland deltaic landscape, shaped almost entirely by the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna (GBM) river system. Its only upland territory—the Chittagong Hill Tracts—belongs to the Arakan (Rakhine–Yoma) mountain system, which is geologically separate from the Himalayan range.

Historically, Bengal also included the Terai–Dooars belt and the Darjeeling Himalayan region (incorporated during British rule), both of which represent true Himalayan foothill and sub-montane environments characterized by heavy rainfall, dense forests, and rich faunal communities.

For thousands of years, the powerful GBM river system, combined with intense monsoon rainfall and continuous alluvial deposition, has shaped Bengal’s ecological identity. These forces created the region’s floodplains, delta, wetlands, and exceptionally fertile soils, while driving its distinct seasonal ecological cycles—making Bengal one of the most dynamic and productive natural landscapes in the world.

Biodiversity of the Bengal Region — Scientific Version

The region historically known as Bengal—comprising present-day West Bengal (India) and Bangladesh—constitutes a biogeographically complex landscape shaped by the interaction of Himalayan orogeny, monsoonal hydrology, and the geomorphological dynamics of the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna (GBM) river system. This continuum incorporates high-elevation Himalayan foothills, extensive fluvial plains, freshwater swamp complexes, estuarine systems, and the world’s largest mangrove delta.

Physiographic Setting

Northern West Bengal (including Darjeeling, Kalimpong, Jalpaiguri, and Alipurduar) represents the easternmost margin of the Central and Eastern Himalaya. The region supports a gradient of montane ecosystems, including:

Temperate and subtropical broadleaf forests

Montane cloud forests

Rhododendron–oak assemblages

High-biodiversity ecotones with significant endemism in flora and fauna

These habitats sustain Ailurus fulgens (red panda), diverse Himalayan passerines, pheasants, and a rich orchid flora.

Bangladesh, by contrast, is primarily a Holocene alluvial plain formed by the GBM system, one of the largest active deltas on Earth. Its only upland physiographic unit, the Chittagong Hill Tracts, belongs to the Arakan (Rakhine–Yoma) fold belt and is biogeographically associated with the Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspot rather than the Himalaya.

Historically, the Bengal region also encompassed the Terai–Dooars belt and Darjeeling Himalayan zone, which represent true sub-Himalayan foothill environments characterized by high precipitation, seasonally inundated grasslands, and dense semi-evergreen forests.

Hydro-Ecological Processes

For millennia, the monsoon-driven GBM river network has been the dominant ecological and geomorphological driver, governing:

Alluvial deposition and soil formation

Floodplain hydrodynamics

Seasonal wetland expansion and contraction

Estuarine nutrient fluxes

These processes generate one of the world’s most productive landscapes, with high primary productivity and constantly shifting habitat mosaics.

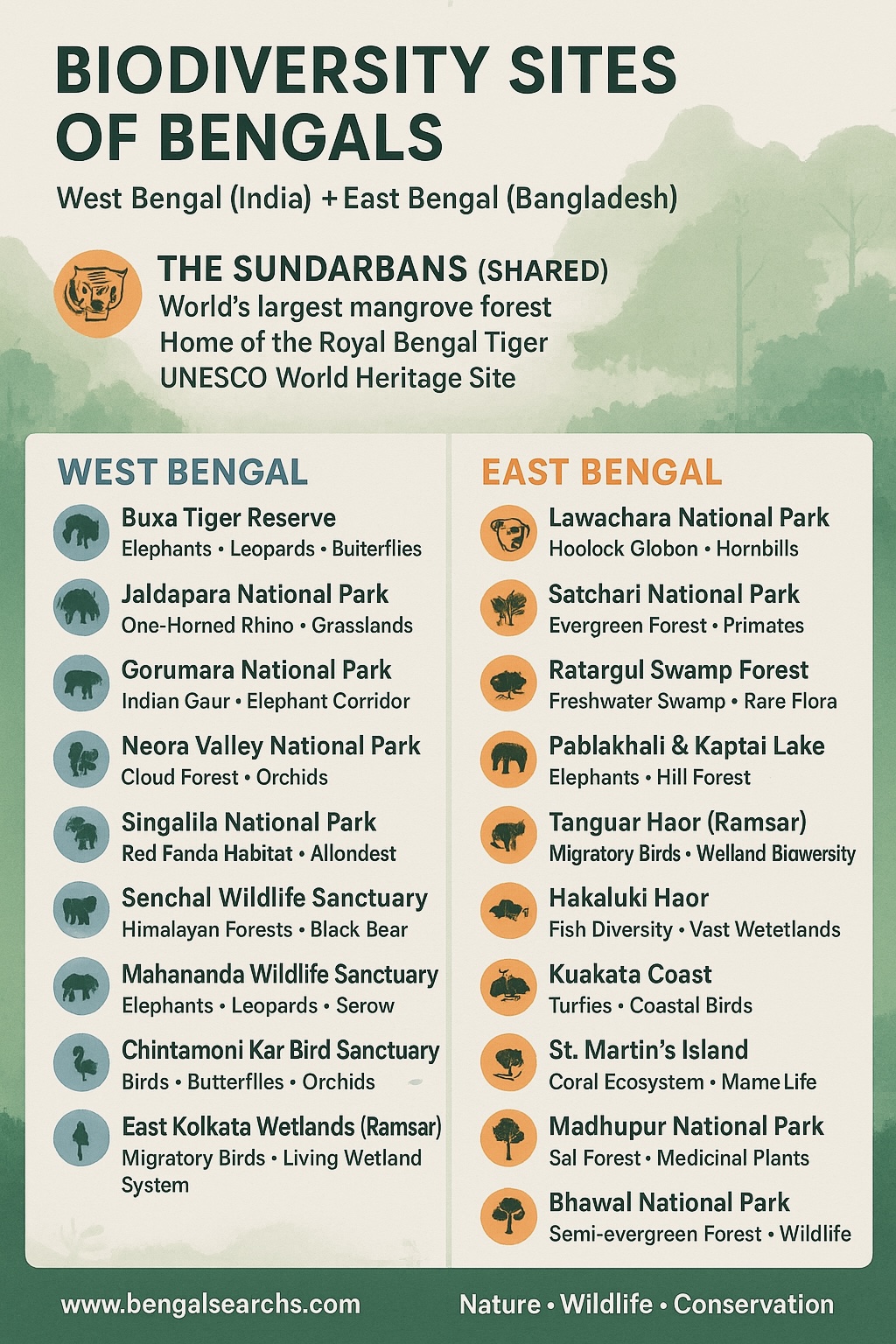

Major Ecosystem Types

The Bengal region hosts a wide spectrum of ecosystems, including:

Montane cloud forests (≈2,000–3,600 m)

Subtropical and temperate broadleaf forests

Moist deciduous and semi-evergreen forests

Alluvial grasslands of the Terai–Dooars system

Sal (Shorea robusta) forests of the Madhupur–Bhawal plateau

Floodplain wetlands, haor basins, and multiple Ramsar-designated sites

Mangrove forests of the Sundarbans

Coastal and marine ecosystems of the northern Bay of Bengal, including limited coral-bearing islands

Biodiversity Patterns

This environmental continuum supports high species richness and notable endemism. Key taxa include:

Large mammals:

Panthera tigris tigris (Royal Bengal Tiger), Elephas maximus, Rhinoceros unicornis, Bos gaurus

Primates:

Hoolock hoolock (Western Hoolock Gibbon), Macaca spp., Trachypithecus spp.

Avifauna:

Over 700 recorded bird species, reflecting both Himalayan and Indo-Burman affinities and the importance of the Central Asian Flyway.

Herpetofauna & Invertebrates:

High endemism in amphibians, butterflies, and hill-forest flora, particularly orchids.

Aquatic biodiversity:

The haor wetlands, major rivers, and estuarine systems harbor rich fish assemblages, invertebrates, and migratory species vital to regional food webs.

Wetland complexes such as Tanguar Haor, Hakaluki Haor, and the East Kolkata Wetlands function as key sites for carbon cycling, nutrient retention, groundwater recharge, and avian migration.

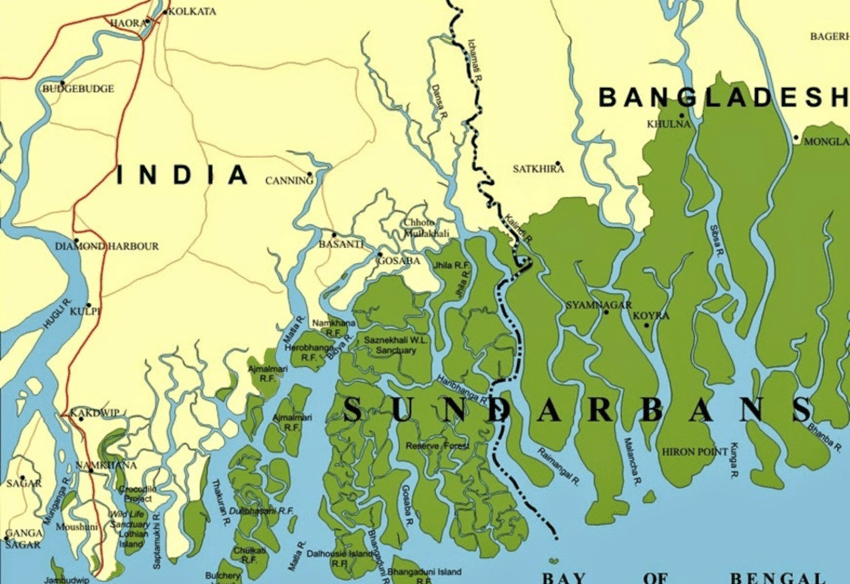

The Sundarbans: A Keystone Estuarine System

The Sundarbans, the world’s largest continuous mangrove ecosystem, forms a highly productive estuarine interface between riverine freshwater inputs and marine tidal fluxes. It provides:

Carbon sequestration of global significance

Cyclone and storm-surge mitigation

Critical habitat for apex predators and estuarine specialists, including Panthera tigris tigris, Crocodylus porosus, and several dolphin species

Transboundary Ecological Connectivity

Despite political demarcations, Bengal functions as a transboundary ecological unit. Shared river basins, migratory fauna, and interconnected wetlands underscore the need for coordinated, ecosystem-based conservation frameworks between India and Bangladesh. Effective management demands integrated approaches to sediment dynamics, upstream–downstream hydrology, climate resilience, and cross-border biodiversity protection.

An independent researcher and environmental writer specializing in the ecology, geography, and natural history of Bengal. His work focuses on Himalayan foothill ecosystems, deltaic landscapes, and the biodiversity shaped by the Ganges–Brahmaputra–Meghna river system. He is dedicated to presenting complex ecological processes in clear, engaging narratives that highlight the region’s conservation and climate challenges.

— DRx Shajahan Biswas